Jackson: WWII combat artist dies

By KRISTY GRAY and MARGARET MATRAY

Star-Tribune staff writers

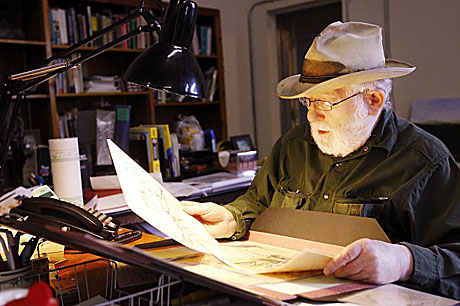

Harry Jackson, one of America’s great artists, died Monday at the V.A. Hospital in Sheridan. He was 87.

“Harry was a real person who managed to parlay great talent into a great life,” said Bruce Eldredge, executive director and CEO of the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody.

“He was larger than life, absolutely. He was a real character, in the sense that he was very profane, very bold and very passionate about what he did and who he was.”

Jackson, a World War II Marine Corps combat artist, is known for his Western paintings and sculptures, abstract expressionism and realist works. His art can be found at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Denver Art Museum and others, and in collections owned by the Saudi Arabian royal family, Queen Elizabeth II, the Italian federal government and the Vatican.

The Whitney Gallery of Western Art at the Buffalo Bill Historical Center in Cody holds the largest museum collection of Jackson’s work in the United States.

Jackson was born in 1924 in Chicago. At 14, he ran away from home.

In February 1937, he saw Charles Belden’s photo essay, “Winter Comes to a Wyoming Ranch,” in Life Magazine. The photos of cattle winding through the snow on the Pitchfork Ranch, a howling coyote and a cowboy rescuing a calf captured Jackson’s imagination.

He hitchhiked to Wyoming and learned to cowboy at the Pitchfork.

“I said, ‘I’m going to go there someday and earn a living as a cowboy,” Jackson told the Star-Tribune in October.

“And I did.”

Throughout his life, he would live in Los

Angeles, study under the great American artist Jackson Pollock in New York City, and move to Europe to take his art in a whole new direction. But he always came back to Wyoming.

“I don’t know that you could say that he ever left,” said his son Matthew Jackson who runs Harry Jackson Studios in Cody.

The Star-Tribune featured Jackson in its “They Served With Honor” series on Nov. 7. The stories chronicle the World War II experiences of Wyoming men and women.

Jackson was the youngest Marine Corps combat artist, serving with Maj. Gen. Holland M. “Howlin’ Man” Smith’s V Amphibious Corps. The mission of a combat artist, apart from being a Marine, was to create art. The program began as a way to keep the home front informed about what the Marine Corps did overseas.

Sixty men served as combat artists in World War II, and more than 100 have participated since.

On Nov. 20, 1943, Jackson joined the 2nd Marine Division in the attack of Betio Island, Tarawa Atoll. The assault took 76 hours and left nearly 8,000 dead.

Marine Whitey Kroenung died next to Jackson, his head blown away by mortar fire. Jackson painted the moment in “Salvatur Mundi Crucified in Betio Amnion,” a painting 6 feet tall that hangs in Jackson’s Cody museum.

In 1944, Jackson saw a painting by Pollock and decided he wanted to meet the famous artist. He made it to New York City four years later and learned from Pollock himself. Jackson became known as one of a group of great artists from the time, a group that included Pollack and Thomas Hart Benton, America’s great regional painter of Midwestern subjects.

“Harry being Harry, he left that group,” Eldredge said. “He said, ‘I’m not going to paint like Pollock,’ and Pollock didn’t really like him for that.

“From my perspective, Harry Jackson will always remain a great American artist. He really is one of those people that when you hear of their passing, you think, ‘You know, there’s an end of an era.”

Among Jackson’s most well-known pieces are the “The Italian Bar” oil painting of the Genovese crime family; his 10-foot-tall painted bronze of Sacagawea; the 22-foot-tall “John Wayne: The Horseman” monument in Beverly Hills, Calif., and “Stampede” and “Range Burial,” the story of life and death in two bronzes and two large oil paintings, which Eldredge called seminal images of the American West.

Funeral arrangements are pending with Ballard Funeral Home in Cody. The family expects to have a private service followed by a public memorial service sometime this summer.

Jackson was the father of five children, and they are privately sharing stories now, said his son Matthew Jackson. They ask for some time to themselves, some time to grieve their father, who also happened to be a great American artist and personality.

“Certainly, we didn’t really share him with everybody else. He was very much, things were about him. We were involved in the whirlwind that was his life, just like everybody else,” Matthew Jackson said.

Jackson wasn’t easily labeled. He created realist and Western paintings and sculptures, wrote the book on the ancient lost-wax method of bronze casting and revived polychrome sculpture — applying paint to the surface of his works.

He wouldn’t want to be called a Western artist or an abstract expressionist, though he was called both.

“Like many great personalities, he was a genius when it came to his art. He had a lot of suffering in his life, a lot of pain, but a lot of creativity came out of that,”

Eldredge said.

Eldredge, Matthew Jackson and Pollock biographer Henry Adams of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland are working on a book about Jackson’s life, the first in several decades.

They spent almost a whole day with Jackson in December, recording Jackson’s oral history for the book. That video footage is the last of “Harry being Harry,” Eldredge said.

Almost every action Jackson took was deliberate. When he wanted to be a Marine, he hitchhiked back to Chicago to join. When his mother wouldn’t sign the papers, he waited until he was 18 and joined anyway.

“I don’t decide anything,” he told the Star-Tribune last fall. “I just do it.”

After a year of failing health — through periods in which he would grow stronger and then fall weak — Jackson was transferred to the Sheridan VA hospital in October. He seemed to do well for a while, said his son. Then in January, he caught a cold and never really recovered.

“He was at a point, he was done fighting and just refused food and drink,” Matthew Jackson said.

“He’s always been one who wants to be in control … things get done his way and that was the most important part of it. It certainly was in keeping with the experience of his life.”